The Birth and Death of a Dock

By R.B. Oram | Published in History Today Volume: 18 Issue: 8 1968

R.B. Oram recounts an episode in the history of British shipping.

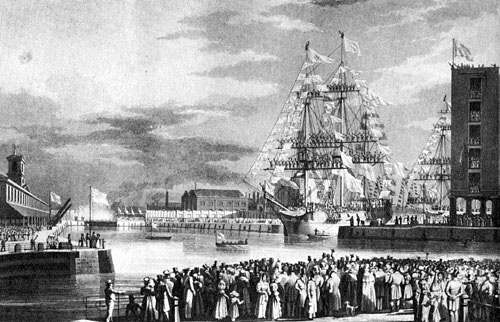

In 1805 the London dock was opened at Wapping, to ships from the Mediterranean, North Africa and the near Continental and coastal ports. It was followed in 1828 by the St. Katharine Dock built on the western side of the London Dock and hard up against the Tower of London. In 1864 the two proprietary companies amalgamated to form the London and St. Katharine Docks.

This complex of entrances, cuttings, quays and warehouses with a total area of 125 acres (water area 45 acres) and four miles of quays (26 berths for ships up to 360 ft. long) is to be sold by the owners, the Port of London Authority. The target set is September 30th, 1968, with all warehoused goods cleared by the end of the year.

These docks, known for a century and a-half throughout the Seven Seas, were built for permanence. Their builders knew nothing of ‘limited obsolescence’—putting up premises whose continued usefulness could be reviewed each decade. They built for the ships of the period whose average size was not, by 1844, more than 241 tons. Inexorably this has risen; by 1903 the average size of ocean-going ships was 1,300 tons, by 1950, 2,700 and by 1963, 3,700 tons.

By 1939 the London and St. Katharine Docks had served well the purpose for which they had been built. Everything that has happened in the world of shipping since 1945, bulk carriers of 200,000 tons, container ships whose cargo consists of units of 25-30 tons (instead of the homely box of oranges or the basket of Spanish onions), has hastened the inevitable decision the Port of London Authority have now taken, to close this dock control. There is sadness that so permanent a part of London, where six generations of labourers and staff have earned a living and where the wonders of an expanding world, of incalculable value, were set before Victorian eyes, is to close down.

Figuratively speaking, at five o’clock on the evening of December 31st, 1968, the Dock Manager will for the last time turn the key of the massive Main Gate and the London and St. Katharine Docks and all they stood for will be no more. It will be the end of an epoch, the end of the small-ship phase in English commerce that began in the wool and wine trade of Henry II, brought about by the intensive struggle, since 1945, to find a larger cargo unit. For three thousand years cargo has been made up in units that could be manhandled. Ships and docks have been built to conform to this limitation. The unit load and the container have swept away in the short space of twenty years the practice of three millennia.

It is interesting that so radical a change has been so concisely marked. Sailing ships lingered commercial for more than a hundred years after the first steamship crossed the Atlantic, just as bows and arrows were used by a Siberian contingent of the Russian Army at the Battle of Leipzig, nearly five hundred years after the first cannon had figured at Crecy. Never again will docks after the pattern of the London and St. Katharine be built in a maritime country.

Success had followed the opening of the West India Docks, as early as 1802, for ships engaged in the lucrative sugar trade from the West Indies.1 A safe harbourage had been provided for the many hundred ships previously laid in tiers on the river buoys, where discharge was slow and they were at the mercy of storms, floating ice and fire.2 Pilferage from the ‘Mudlarks’, the disreputable river-workers of the eighteenth century, rose to a level of thirty per cent of the incoming cargoes—to the great loss of the Revenue, as much of the imports consisted of sugar, rum, brandy and tobacco.

In the new dock ships were assured of a constant level of water, and were not subject to the erosion of their hulls through being stranded twice every twenty-four hours. The idea of an enclosed dock where work could go on, continuously, under strict supervision (river-working was restricted to daylight hours and then only at Legal quays, later extended to ‘sufferance’ wharves), appealed to the commercial community. There was, therefore, little opposition to a Bill for making the London Dock ‘as near as may be to the City of London and the seat of Commerce’; this received the Royal Assent on June 20th, 1800.

London Dock has always been accessible on foot to the City, where commerce has tended to congregate around Tower Hill and Fenchurch and Leadenhall Streets.3 For the first century of its existence horse-drawn wagons conveyed the cargoes stored in its capacious warehouses for the short distances to the town premises of importers. The original design made by D. A. Alexander, the architect of Dartmoor Prison (his works have several features in common), provided only for the Western Dock and an entrance via a large Basin at Wapping, less than a mile by water from London Bridge.

The original construction provided for warehouses to be placed some 60 ft. back from the dock water, with a cart road and narrow sheds, for sorting landed cargo, in between. The importance of tobacco was recognized by the Tobacco warehouse on the East Quay which held 24,000 hogsheads of this highly dutiable commodity. Security hitherto unknown both for ships and cargo, with facilities for storing, sampling and working valuable merchandise, was offered by the London Dock Company when they opened their dock on January 31st, 1805.

The building by Rennie had taken longer than was expected. The excavation of some thirty-five acres and the building of three miles of quays with their contiguous warehouses literally had to be done by hand. Armies of ‘navvies’ (a term invented for the much-sought-after Irish labourers who subsequently ‘navigated’ the railroads across the English countryside) lined up with their shovels, working a spit at a time over the area. The spoil was removed by horse-drawn wagons—the only form of power available.4

The London Dock Company met with little difficulty in acquiring the land at Wapping. Although the Main Entrance to their dock was within five hundred yards of the Tower of London there is record only of a brewing industry in the neighbourhood. Licensed by Henry VII in 1492 it had considerable production in Tudor times, exporting five hundred tuns at a time to Antwerp, presumably for the English Army in Flanders.

It was not until 1827 that the Eastern Dock was built. The connexion with the Thames at Shadwell made a considerable saving to shipping entering the dock. By 1815 steam-driven vessels were seen on the Thames; they were quickly adapted to the towage of sailing ships. The use of steam for cargo vessels does not seem to have been visualized until the 1840’s. The expanding imports of tea that followed the introduction of the tea-plant to the receptive soil of India at this time were housed in the Tea Warehouse which had been built in 1805.

The wool warehouses were opened in 1858 for what was to become a vast traffic in the storage, showing and public sales of imported wool. By the middle of the century the dock was flourishing. Steam had by then arrived as a propulsive power for ships.5

The nineteenth century was an era of dock building; and in 1825 the newly formed St. Katharine Dock Company began demolition and excavation of the area between the western limit of the new London Dock and the eastern side of the Tower Moat. To obtain the use of the site, St. Katharine Hospital (built in 1148 by Matilda of Boulogne, wife of King Stephen), together with 1,250 habitations, were pulled down.

Eleven thousand and three hundred people had to find homes elsewhere; and much opposition, ineffectual as it turned out, was organized, especially as there was no effort made to find accommodation for them elsewhere. There was much sentimental support for the Hospital, for it had escaped the Dissolution of 1534 (Henry VII had confirmed the liberties and the franchises in 1526). It had escaped a direct assault by the Gordon rioters of 1780, who had attacked it as ‘having been built in Popish times’.

Despite the flooding of eight acres of the site by an extra high tide on October 31st, 1827, the eleven acres of water space, the one mile of quay and the vast Bastille of many-storeyed warehouses with their underground vaults, were opened for traffic in 1828.

The technology of cargo-handling was then in its infancy and the proprietors made a daring innovation in the housing of ships’ cargoes. London Dock had constructed narrow quay transit sheds, in which goods could be sorted to marks before transfer to the warehouse. Greatly daring, the St. Katharine Company took the ship’s cargo directly into the upper floors of the adjacent warehouse, thereby considerably speeding the discharge of the ship alongside. Unfortunately, when sorting had to be done, as it too often did, there was delay and double-handling; the experiment was never subsequently repeated.

By the mid-century, the role of this dock was as clearly defined as that of London Dock. Although small ships kept the dock berths occupied for another seventy years, warehousing of goods sent up from the lower docks became the mainstay. In 1900 the dock was handling 1 million tons of shipping, with a revenue of over £1m. and with 15,000 pipes of wine and 10,000 puncheons of nun in its vaults.

Steamships were soon to outstrip sailing vessels in size, the largest sailorman of that period being about 1,500 tons. The increase in ships’ length and draught made demands on docks that London Dock could not meet. The Entrance Lock was a very real bottleneck. The position had been recognized by the building of the Royal Victoria Dock, by a separate company, opened in 1855. Seven miles below London Bridge, it had 28 ft. of water and could take ships up to 450 ft. long, 100 ft. longer than at London Dock.

The latter dock had by this time achieved a considerable trade—which riverside wharves along the Upper and Lower Pool were doing their best to capture—with the Mediterranean, North African and Scandinavian ports. The value of its secure warehouse space was recognized by merchants who entrusted the growing wealth of the five continents to its care. If the dock had to be bypassed by the larger ships now building, its proprietors could still concentrate on the housing of valuable imports.6

While continuing to receive small ships, the London Company built, and opened in 1880, the Royal Albert Dock, a continuation of the Royal Victoria Dock, to the Galleons Reach. This new dock was essentially for transit goods, those for warehousing being lightered to London Dock. To further their policy the London Dock Company, in 1864, had amalgamated with the St. Katharine Dock Company and the Victoria Dock Company.

With the opening of the Royal Albert Dock, whose entrance was eleven miles below London Bridge, the largest ships of the times could be berthed in the eighty-seven acres of deep water. The London and St. Katharine Docks Company had a pre-emptive claim on goods for warehousing. As Victorian standards of living went up, the tonnage and variety of these goods increased.

Meanwhile, the East and West India Dock Company, goaded by the building of the Royal Albert Dock, and also by the growing competition from the Millwall and the Surrey Commercial Docks, built Tilbury Dock, twenty-six miles from London Bridge. It was opened in 1886, but for some time remained empty. By 1889 it had bankrupted the parent company who were constrained to approach the London and St. Katharine Dock Company for a working agreement, which, however humiliating, would keep their new venture afloat until it could be made to pay.7

The new management became known as the London and India Docks Joint Committee. So awkward a compromise could hardly be a success. The London members saw no point in developing the property jointly held, while the India members chafed under the inert regime imposed by the majority. Shipping had advanced little during the last decade of the nineteenth century and demands made on dock accommodation were met without difficulty.

The unhappy partnership was brought to an end with the formation of the London and India Docks Company on January ist, 1901; this owned the London, St. Katharine, East, West and South West India and the Royal Victoria and Albert Docks, leaving only the Millwall and the Surrey Commercial Docks as competitors. They were finally absorbed into the Port of London Authority, an energetic body that began its control over the five dock systems in the port of London on April 1st, 1909.

A large and well-equipped Jetty was built out from the West Quay. Shadwell Basin was developed and many ships’ berths equipped with cranes, the work being substantially completed before 1914. East Smithfield Rail Depot, a few yards outside the Main Gate, provided rail facilities that London Dock had never enjoyed and served as a feeder for exports to the Royal Docks. Only people having business there have ever been allowed into the docks of London. This virtual closing to the public led to much speculation upon the fabulous value of the cargoes handled there; little of this rumour was exaggerated.

Social reform writers were always fond of comparing the wealth locked up in the docks, behind the 20 ft. walls, and particularly at the London and St. Katharine Docks, with the meagre rewards given to the labour and staff who handled these riches. A visitor allowed into these uptown docks could have concluded that amid the gloom of Victorian London the gorgeous East was indeed held in fee.

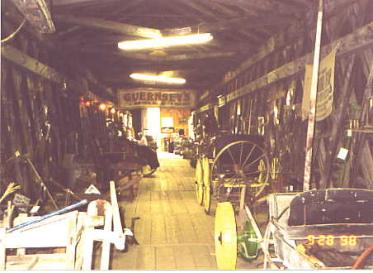

Carpets, teas and silks from China and Japan, perfumes and essential oils, coffee, spices and drugs, were all to be seen in the transit sheds or in process of being sampled, weighed and piled in the warehouses, ‘places of special security’ as Mayhew correctly describes them. Ivory tusks from Africa had their own warehouse and Show Floor, from whence brokers bought at the periodical Public Sales. Staple imports such as wine and wool provided a rich revenue to the Company and work for hundreds of men and staff.

Twenty acres of underground storage space comprised twenty-eight separate vault systems; it was possible to walk, if you knew the way, from the Main Gate, quite near the Tower, to distant Shadwell, without once surfacing. Prior to the partial destruction of the vaults during the Second War, when both docks suffered badly from the Blitz, there were thirty miles of ‘skids’, the name given to the metalled gangways over which the casks of wine were rolled.

The vast stocks of wool, in a special range of warehouses, were housed, sampled and lotted for Public Sale by the Dock Company and its successors. Buyers from the Bradford area and the North flocked to London for examination of the many lots. The annual importation was of the order of 130,000 bales and there was storage, partly under a north light for viewing the texture of the wool, for 20,000 bales. In adjacent warehouses could be seen stocks of tin ingots and heavy metal bottles of quicksilver, both from Spain, canned goods comprising sardines and Mediterranean fruits, dried fruit from Greece, sulphur and sugar, the latter in large hogsheads that gave way in time to the jute bag.

The scent of fresh fruit in season, oranges from Spain, lemons, grapes and onions, pervaded the Western Dock, while the less attractive smell of hides and skins came from the East Quay. The pungent smell of fresh hops from Hamburg always lingered about the St. Katharine Dock, mixed with that of rubber and wine. Indigo, the handling of which coloured the faces and hands of the workers, was a thriving import until superseded by synthetic dyes.

Tobacco was largely housed in London Dock, giving rise to the ‘Queen’s Pipe’, an installation that always fascinated visitors. A huge furnace, kept permanently burning, it consumed tobacco unfit for home consumption or on which duty had not been paid. It came in useful, also, for combustible cargo such as hams that were judged to be inedible or Italian gloves whose owner had declined to pay the duty. There developed a useful trade in the by-products of the Queen’s Pipe—ashes for fertilizers and manure and the nails from the burnt wooden cases which, having been through the fire, were highly valued by gunsmiths.

What of the labour that worked in all weathers, with few or no amenities and no certain prospect of employment for the majority, even at the 4d. per hour that dock wages sank to? Mayhew has given a generally accurate picture in his London Life and Labour8 of the 3,000 or more men that were employed at London Dock. This number fell to around 500 when unfavourable winds kept sailing ships from coming up the estuary.

In the 1870’s, the pay was 16s. 6d. per week. This had dropped from 24s. a week paid at the opening of the dock in 1805. In 1809 one hundred Preference Labourers were appointed and they owed their place on the list to the favour of a Director. Hours of work were from 6 a.m.-6 p.m. in summer and 7 a.m.-5 p.m. in the winter, with overtime as needed. Men could be engaged for as little as half an hour at a time.

With the slump in trade after Waterloo, the conditions in St. Katharine Dock were inferior to London’s. The establishment of 1830 allowed 225 permanent men and 200 Preference Men. The former received 16s. for a week’s work. The St. Katharine Dock Company made up for the paucity of their payments by the loftiness of the moral standard on which they insisted. ‘Honesty and sobriety were indispensable qualifications, the slightest deviation from them will be attended with immediate and irrevocable dismissal’.

No beer was allowed to be brought into the dock, neither empty cans in which wines or other liquids could be taken out. Henry Mayhew remarked on the deterioration that had overtaken labour standards by the 1860’s, as he watched the bestial and sub-human struggles for work of the cosmopolitan crowd, only a few of whom could earn a few coppers by the end of the day. He would have been distressed to have known that these conditions continued substantially until the Second War.

The staff worked in Dickensian conditions although not ill-paid by the standards of the time. They had permanency and a pension. A large draughty office held upwards of 100 clerks who wrote in copperplate in heavy ledgers; these were kept in racks below the desks during the day and in strong rooms during the night. Two large open fires, one at either end, the only heat available, sent most of this up the chimneys.

By ten o’clock on a winter’s morning the staff were blowing on their hands, or slipping down to the underground dining room where a slice of dripping toast and a mug of coffee could be had for a penny. A good lunch was served here for five-pence, albeit the dining room looked out on to a battery of earth closets that provided the only sanitation for the office block. By the standards of 1914 it found ready acceptance.

The area outside the dock was full of interest. Ratcliff Highway, the Regent Street of the Victorian sailor, provided all that he could need.

Wild animal shops, of which the most famous, Jamrachs, was known throughout the Seven Seas; so were the brothels that lined the side streets. Sailors pitched out into the gutters of St. John’s Hill or Artichoke Hill, off the Highway, and tied round the middle with brown paper and string, were alleged by the older clerks to have been a common sight in the 90’s. The robust night life of this part of London proved an attraction to Victorian high society.

At Wapping was the old Execution Dock where river pirates were hung when caught, and nearby the ale-house from which Judge Jeffreys had been torn by the mob in 1689. A more pleasant memory was of James I who is reputed to have hunted a stag from Wanstead and ran him down in Nightingale Lane, now a grim thoroughfare enclosed by the 20 ft. walls of the London and St. Katharine Docks.

On December 31st, 1968, all this will come to an end. The site will be transformed into a housing estate for the Greater London Council.

1 Duties on sugar imported are said to have largely financed the war against Napoleon.

2 In the great storm of 1703 hundreds of ships in the River Thames were damaged, most being driven ashore. In the Howland Great Wet Dock, opened in 1694 at Rother-hithe, no ships were damaged.

3 Tilbury Dock opened in 1886, 26 miles below London Bridge, was dependent entirely on the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway. No roads were included in its original design; the dock was not effectively road served until 1950.

4 As late as 1900, when the Greenland Dock at the Surrey Commercial Dock in London was extended, the method of loading the spoil into metal skips on a primitive rail was still used, except that small shunting engines were employed in place of horses.

5 The large quantities of coal required for the early and inefficient ships’ engines left little room for cargo, before bunkering stations were installed on the main trade routes. Hence the need for carrying valuable cargoes in what space remained from coal. Hence the competition for Her Majesty’s Mails and the emergence of die Royal Mail & Union Castle Mail Steamship Lines.

6 The value attached to the warehousing of ships’ cargoes is illustrated by the attempts of docks companies to entice ships that would hand over their cargoes (of tea, tobacco, wine, sugar etc.) for housing, by the promise of free entry of the ship into the dock.

7 From being the white elephant of the port for over half a century, Tilbury Dock is now the centre for the new business in containers and packaged timber. It is ironic that the lame duck of the 1880’s has now become the business centre of a modernized port that has no use for the London and St. Katharine Docks.

8 Conditions of labour at the time of the Great Strike of 1889, led by John Burns, were described by the author in an article, ‘The Fight for the Dockers’ Tanner’, in the August 1964 issue of History Today.