Magical Realist

Valued Senior Member

How does light pass thru transparent matter like glass and plastic? It seems like the photons would be obstructed by atoms as in normal matter.

Photons don't interact with matter as if they're little solid balls. They interact by being absorbed - usually into molecular bonds. If the photons aren't of the right frequency to be absorbed, they just pass right through.How does light pass thru transparent matter like glass and plastic? It seems like the photons would be obstructed by atoms as in normal matter.

Photons don't interact with matter as if they're little solid balls. They interact by being absorbed - usually into molecular bonds. If the photons aren't of the right frequency to be absorbed, they just pass right through.

One often hears of photons having frequency,

but frequency of what exactly?

Frequency is just an event over time.

But what actual event has that frequency?

I've never had heard a satisfactory answer to this question.

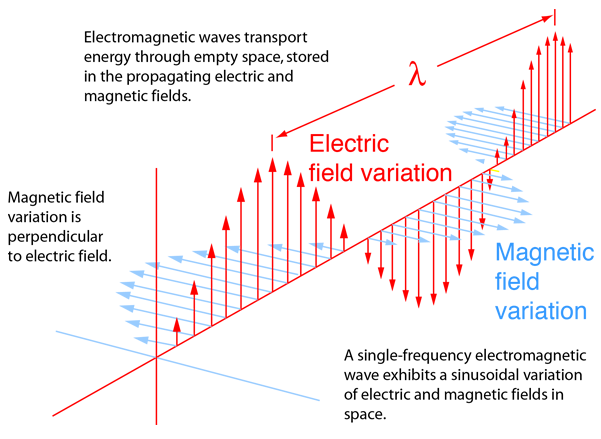

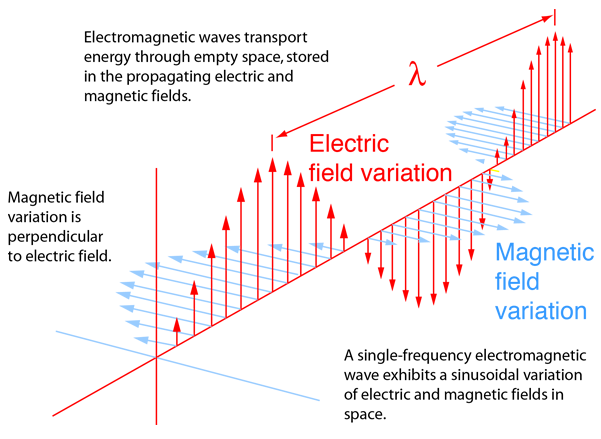

A photon can be described as an excitation of the electromagnetic field. See the simple diagram below.

They propagate at the speed of light and the level of excitation determines their wavelength.

Frequency is just 1/wavelength.

That's not quite right. The photon is not a field. It is an excitation of the electric and magnetic fields. Just as the ripple on a pond caused by dropping a pebble into it is a disturbance of the water surface. The ripple is not the water surface, but an excitation of it.well that does not answer the question

because the magnetic field is said to actually be

the photon too - which is - you must admit - paradoxical

at least - but i am not going to argue any further

as you answered with a quote instead of in your own words

No I didn't. I wrote that.you answered with a quote instead of in your own words

Err... frequency is the speed of light divided by wavelength ($$v=f\lambda$$). You're thinking of the period of a wave.They propagate at the speed of light and the level of excitation determines their wavelength.

Frequency is just 1/wavelength.

The frequency is a wave-like property of the photon, which acts in some respects like a particle and in some respects like a wave. It is related to the wavelength and the speed of light (see previous post).One often hears of photons having frequency, but frequency of what exactly?

I should have just said frequency is inversely proportional to wavelength.Err... frequency is the speed of light divided by wavelength ($$v=f\lambda$$).