You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Palestinian territory between 135 and 625 AD

- Thread starter arauca

- Start date

Try Google:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Palestine

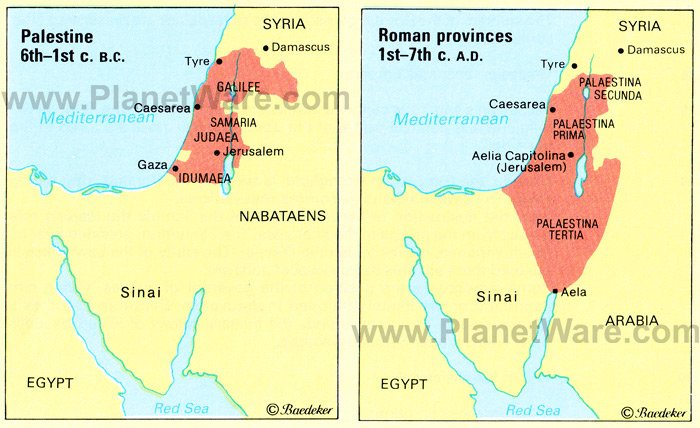

In 70 AD, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259-272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Palestine

In 70 AD, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259-272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction.

Try Google:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Palestine

In 70 AD, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259-272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction.

Dats some good weed Man ! Yeah good post !!

Try Google:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Palestine

In 70 AD, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259-272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction.

From what I read ; After the revolt 135 Jews were not allowed to live in the Judea, so the question is was thee a large reshuffling of peoples ? or was it only they were not permitted to ive in Jerusalem ?

From what I read ; After the revolt 135 Jews were not allowed to live in the Judea, so the question is was thee a large reshuffling of peoples ? or was it only they were not permitted to ive in Jerusalem ?

Are you talking about Jews or Judeans? Not all of the Judeans under Hadrian were monotheists, although they did practise circumcision which they learned from the Egyptians. So Jewish Judeans were exiled from Judea, not from Palestine, which included other Roman provinces

While bible history afficionados claim that it was the Romans who named Judea as Palestine, that is incorrect since 600 years before that, Herodotus named Palestine in his works as later on, did other writers.

The first clear use of the term Palestine to refer to the region synonymous with that defined in modern times was in 5th century BC Ancient Greece. Herodotus wrote of a 'district of Syria, called Palaistinê" in The Histories, the first historical work clearly defining the region, which included the Judean mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Approximately a century later, Aristotle used a similar definition in Meteorology, writing "Again if, as is fabled, there is a lake in Palestine, such that if you bind a man or beast and throw it in it floats and does not sink, this would bear out what we have said. They say that this lake is so bitter and salt that no fish live in it and that if you soak clothes in it and shake them it cleans them," understood by scholars to be a reference to the Dead Sea.[11] Later writers such as Polemon and Pausanias also used the term to refer to the same region. This usage was followed by Roman writers such as Ovid, Tibullus, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Dio Chrysostom, Statius, Plutarch as well as Roman Judean writers Philo of Alexandria and Josephus[12]. Other writers, such as Strabo, a prominent Roman-era geographer (although he wrote in Greek), referred to the region as Coele-Syria around 10-20 CE.[13][14] The term was first used to denote an official province in c.135 CE, when the Roman authorities, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, combined Iudaea Province with Galilee and other surrounding cities such as Ashkelon to form "Syria Palaestina" (Syria Palaestina), which some scholars state was in order to complete the dissociation with Judaea.

What the Romans did was to designate it an official province.

Last edited:

Are you talking about Jews or Judeans? Most of the Judeans exiled by Hadrian were not monotheists, although they did practise circumcision which they learned from the Egyptians. So Judeans were exiled from Judea, not from Palestine, which included other Roman provinces

While bible history afficionados claim that it was the Romans who named Judea as Palestine, that is incorrect since 600 years before that, Herodotus named Palestine in his works as later on, did other writers.

What the Romans did was to designate it an official province.

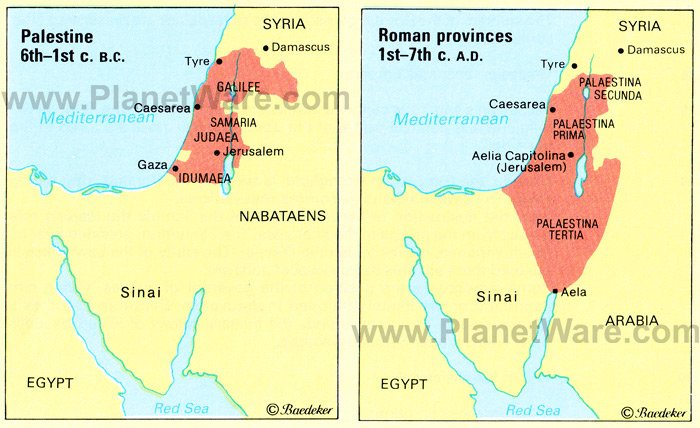

You are saying most of the exiled were not monotheists, well I looked at you map the are in my mind is the blue one , which is marked Roman Judea ,

I have the impression the people who lived there were Jews and Christians and since Bar Kokhba liberate the area for the Jews, and at one time it was thought he was the Messiah , so I would expect the popilation there were monotheists ?

Beside I like your maps.

Yeah sorry, I misspoke and made the corrections. The Jewish Judeans were exiled from Judea but temples dedicated to other gods worshipped by Judeans flourished - temples dedicated to Astarte for example were built under Hadrian see this coin:

Struck in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) just after Bar Cocheba rebellion when an Astarte temple had just been built on the site of the Holy Sepulchre. The hexastyle temple depicted on the reverse of this coin my be the Temple of Astarte in Aelia Capitolina.

http://coins.lib.virginia.edu/display-uva?id=nfic_50_65

The Christians came from Nazareth. There were the Netzarim or the Nazarene in Hebrew but after Hadrian, the Church was born and that led to Christianity as we know it. The Netzarim became the "Hellenists" which is Roman Christians.

Not sure how reliable this is:

http://www.netzarim.co.il/Museum/Sukkah06/Sukkah06new.htm

Struck in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) just after Bar Cocheba rebellion when an Astarte temple had just been built on the site of the Holy Sepulchre. The hexastyle temple depicted on the reverse of this coin my be the Temple of Astarte in Aelia Capitolina.

http://coins.lib.virginia.edu/display-uva?id=nfic_50_65

The Christians came from Nazareth. There were the Netzarim or the Nazarene in Hebrew but after Hadrian, the Church was born and that led to Christianity as we know it. The Netzarim became the "Hellenists" which is Roman Christians.

Not sure how reliable this is:

First, in 135 C.E., they forcibly displaced the innate authority of the Jewish פָּקִיד ha-Nәtzâr•im′ , arrogating that authority to the gentile office of Hellenist επισκοπος—the birth of the Church.

Thereafter, the Christian founders, being gentile and Hellenist Romans, freely syncretized and morphed the surrounding Roman and Greek mythologies that were familiar to them. Their only serious problem was the impossible chasm between them and the Jews… and Judaism. This they partially solved, among the gentiles and few Hellenist Jews of their fledgling church, easily, because the Romans were utterly ignorant of Hebrew. Translating—and interpreting and redacting—into Greek enabled them to reject Judaic Hebrew, displacing it with their gentile Hellenist Greek.

Finally, the 180° reorientation from Tor•âh′ to antinomian Hellenism being secured, they reoriented from the "Holy City" of the Jews, Yәru•shâ•la′ yim, to the "holy city" of their pagan pantheon – Rome. This reorientation, however, required an authority Christians lacked (see "30-99 C.E." section). By the 3rd-century C.E., this need had became so unavoidable Hegesippus was forced to fabricate a succession of "popes" in Rome (see "Fabrication of Popes" section) to accompany the claim that Rome, the "Holy City" of Zeus and Jupiter and an array of pagan idols, had always been the "Holy City" of the Church.

Having completed the apostasy of supposedly transferring authority from Jews to Hellenist (Greek-speaking) gentile Christians, the "Holy City" from Yәru•shâ•la′ yim to the seat of idolatry and Sâ•tân′ , and no longer restricted by Judaic interpretations of millennia, they began freely redacting the Greek stories that circulated among Hellenist Jews, compiling their Greek Hellenist-Christian NT from their Hellenist and gentile perspective.

The trick: by subtly translating two Greek words as "gentile," and creatively interpreting a Greek grammar form that can be either locative, dative or instrumental, they were able to interpose "gentiles" to their gentile audience where, originally, either "[Jews] among the goy•im′ ," i.e., the Diaspora, or "Hellenist Jews" (of the Diaspora) had been obvious to the Jewish audience. By this combination of creative translation deceptions, the gentile Roman Christian Church founders displaced the Jews:

http://www.netzarim.co.il/Museum/Sukkah06/Sukkah06new.htm

Last edited:

Since the Netzarim POV was from the Jewish side - here is the POV from the Christian side:

http://www.ccel.org/ccel/renan/hadrian_pius.xvi.htmlThe Jewish catastrophe of the year 134 was almost as advantageous for the Christians as that of the year 70 had been. In their eyes, everything that savoured of the law of Moses must have appeared to be abrogated without a chance of return; faith alone, 140and the merits of the death of Jesus, were all that remained. Hadrian did a signal service to Christianity when he prevented a Jewish restoration of Jerusalem. Ælia, peopled, like all the colonies were, by veterans and common people from different parts, was no fanatical city, but, on the contrary, a centre disposed to receive Christianity. As a rule, the colonies were inclined to adopt the religious ideas of the countries to which they were transported. They would not have thought of embracing Judaism, but Christianity, on the other hand, received everybody. During the whole course of its three thousand years of history, it was only for those two hundred years, from Hadrian to Constantine, that human life had unfolded freely within its bosom idolatrous forms of worship, established on the ruins of the Jewish religion, complacently adopted more than one Jewish practice. The Pool of Bethesda continued to be a place of healing, even for the heathen, and to work its miracles as in the times of Jesus and of the apostles, in the name of the great impersonal God. For their part, the Christians continued, without exciting any feeling except one of pious admiration in the breasts of the worthy veterans who formed the colony, to perform their cures by means of oil and sacred washings. The traditions of that Church of Jerusalem were distinguished by a special character of superstition, and, of course, thaumaturgy. The holy places, especially the cave and the manger at Bethlehem, were shown, even to the heathen. Journeys to those places sanctified by Jesus and the apostles, began within the first years of the third century, and replaced the former pilgrimages to the temple of Jehovah. When St Paul took a deputation of his churches to Jerusalem, he took them to the Temple, and surely he was thinking neither of Golgotha nor of Bethlehem. Now on the other hand, men strove to retrace the life 141of Jesus, and a topography of the Gospel was formed. The site of the Temple was known, and, close to it, the stela of James, the Martyr, brother of the Saviour, was venerated.

Thus the Christians reaped the fruits of their prudent conduct during the insurrection of Bar-Coziba. They had suffered for Rome that had persecuted them; and in Syria, at least, they found the prize of their meritorious fidelity. Whilst the Jews were punished for their ignorance and their blindness, the Church of Jesus, faithful to the Spirit of her Master, and, like Him, indifferent to politics, was peaceably developing in Judea and the neighbouring countries. The expulsion of the Jews was also the lot of those Christians who were circumcised and kept the Law, but not of those uncircumcised Christians who only practised the precepts of Noah. That latter circumstance made such a difference for their whole life that men were classified by it, and not by faith or disbelief in Jesus. The Hellenistic Christians formed a group in Ælia, under the presidency of a certain Mark. Till then, what was called the Church of Jerusalem had had no priest who was not circumcised, and, more than that, out of regard for the old Jewish nucleus, nearly all the faithful of that Church united the observation of the Law with belief in Jesus. From that time the Church in Jerusalem was wholly Hellenistic, and her bishops were all Greeks, as they were called. But this second Church did not inherit the importance of the former one. Hierarchically subordinate to Cæsarea, she only occupied a relatively humble position in the universal Church of Jesus, and nothing more was heard of the Church of Jerusalem till two hundred years later.

Fraggle Rocker

Staff member

Jerusalem is just one city. Judea is a large area. At various times in the past it was a province or a nation; today it comprises a major portion of Israel. The Jews were not permitted to live anywhere in Judea.From what I read, after the revolt in 135 Jews were not allowed to live in Judea. So the question is: was there a large reshuffling of peoples, or was it only that they were not permitted to live in Jerusalem?

Virtually all linguists agree that the etymology of the name "Palestine" is nothing more or less than a Romanization of "Palaistine," which in turn was merely the Greeks' Hellenization of "Philistia," the name of the land for which "Philistine" is the ethnonym.While bible history afficionados claim that it was the Romans who named Judea as Palestine, that is incorrect since 600 years before that, Herodotus named Palestine in his works as later on, did other writers.

The origin and ancestry of the Philistines is not clear. They show up in history at the end of the Bronze Age, as the Egyptians withdrew from Canaan, and they eventually came to rule much of the land, becoming the primary enemies of the Israelites. They absorbed the culture of the surrounding tribes and ultimately vanished into the Levantine melting pot, so that today we can't find any "Philistine DNA" to help identify their ethnicity. There was a lot of migration in the region in those days so they could have come from just about anywhere, including Anatolia, North Africa, the various Mediterranean islands, or the Levant including Canaan.

It's tempting to assume that the Palestinians are the descendants of the Philistines. But the only evidence to support that assumption is their ethnonym, and the people were clearly named after the land, not vice versa. Just as today's Britons are not descended from the original Celtic Brythonic people but are the descendants of Germanic Anglo-Saxons who took the name of their land, today's Palestinians are not descended from the Philistines, but simply have a phonetically modernized version of their name because they live in Philistia.

They don't show up in history until the Muslim Conquest, and they may well be the descendants of both Jews and Christians in Judea whom the Arabs converted to Islam. Their DNA is more closely related to that of the Jews than to anyone else, which lends support to this hypothesis since obviously a significant portion of the Christians in Judea would have been converted Jews.

Fraggle, what is the evidence for the "Philistines" outside the Bible? In fact, what is the evidence for an historical Canaan? I'm asking because I haven't been able to locate either.

The first appearance of the word Philistines appears to be in the Greek Septuagint, which is predated by the Greek Herodotus clearly writing Palaestine. Since both come from Greek they should not be the same unless the dialect of the Septuagint varied widely from that of Herodotus' Histories

The first appearance of the word Philistines appears to be in the Greek Septuagint, which is predated by the Greek Herodotus clearly writing Palaestine. Since both come from Greek they should not be the same unless the dialect of the Septuagint varied widely from that of Herodotus' Histories

Last edited:

Yazata

Valued Senior Member

Can some one lead me to read historical events taken place in Palestine during Roman period between 135 AD and 625 AD

I'd suggest consulting the massive academic literature on the period. Adding to Fraggle's good post...

The period from bar Kochba to the Arab invasion was very complex on the local village level. Archaeologists are still learning about precisely who was living where and doing what. In general though, it can probably be generally said that this was a period of growing Christian dominance in the area. That's certainly true in political terms in the late antique period from Constantine to the Arab conquest. In terms of numbers, Christian numbers grew fairly rapidly as this was an early center of Christanization in the pagan empire, and they were clearly a very solid majority in the early 600's. Jews didn't disappear though and remained strong in pockets, remaining the majority in much of Galilee throughout the period, especially the eastern half.

As far as political control went, the area was Roman pretty much throughout. The political history of the empire in these centuries was complex, both on the national and the local levels. Provincial boundaries were repeatedly redrawn and Diocletian reorganized the whole provincial system around 300 or so, typically dividing the older provinces in two and basically doubling their number. So maps of provincial boundaries in the area are kind of a snapshot at particular moments.

From what I read ; After the revolt 135 Jews were not allowed to live in the Judea, so the question is was thee a large reshuffling of peoples ? or was it only they were not permitted to ive in Jerusalem ?

Judea wasn't all that large an area. It extended from up around Bethel (today's Ramallah) through Jerusalem down into the southern hills past today's Hebron. It's about the size of a typical county in the contemporary eastern US or the UK. The Romans did try to expel all the Jews from this region and doubtless large numbers left. Many of them fled east into Parthian-controlled Mesopotamia where a sigificant Jewish population already existed. And large numbers fled south into Arabia. Their history down there is of great interest to historians but remains very obscure. They later turn up as a significant minority in Yemen where a Jewish dynasty actually ruled for a short time. Some even crossed over into Ethiopia. We see the cultural impact of these Arabian Jews in the tremendous influence of Jewish mythology in the rise of Islam some 500 years later.

But although the Romans tried to clear the Jews out of an area of twenty by thirty miles or so and turn Jerusalem into a Greco-Roman city with new pagan settlers, many Jews remained nearby in the general area. I doubt if more than a few thousand pagan settlers were actually brought in and settled in Jerusalem.

Probably many Jews were converting to Christianity around this time, because they welcomed the opportunity to escape the oppressive strictures of Jewish law (which many Jews had come to think of as a curse) and because of a widespread disillusion after the failure of bar Kochba's messianic rising. I think that many of Christianity's early converts in Alexandria and throughout the eastern Mediterranean came from disillusioned Jews after the failure of the risings. The remaining orthodox Jews entered into a whole new period of their religion, centered around study in synagogues and yeshivas and resulting in the compilation of the Talmud. These Jews doubtless drifted back into the Jerusalem area in subsequent years as memory of the expulsion receded. So we can say that while post-war Jerusalem probably did have a Greek-speaking pagan majority for a few decades, the population quickly became very mixed and the longer-term religious tendency in your period was towards increasing Christianization.

Last edited:

Fraggle Rocker

Staff member

The Wikipedia article on the Philistines seems to do a decent job of covering their history prior to their appearance in the Bible. Most of it seems to have been documented by the Egyptians who, among other things, fought a war against a coalition of Sea Peoples, one of which is regarded by historians as the Philistines. The Egyptians won, and the Philistines ended up in Canaan, either by withdrawing there or being captured and sent there.Fraggle, what is the evidence for the "Philistines" outside the Bible?

Again, Wikipedia credits the Egyptians with writing about Canaan as far back as the 4th millennium BCE.In fact, what is the evidence for an historical Canaan? I'm asking because I haven't been able to locate either.

As I noted in my prior post, "Philistine" and its variants in our languages is just a phonetic adapatation of the Hebrew name P-L-S or P-L-SH, whose meaning is not clear. The other Afroasiatic languages (Akkadian, Egyptian, etc.) all have recognizable but different renderings of it. Given that to the Greeks it was a foreign name that already had been adapted to several other languages, I don't find it surprising that in two different eras they might have standardized on two slightly different names that can't be blamed on Greek phonetic evolution.The first appearance of the word Philistines appears to be in the Greek Septuagint, which is predated by the Greek Herodotus clearly writing Palaestine. Since both come from Greek they should not be the same unless the dialect of the Septuagint varied widely from that of Herodotus' Histories.